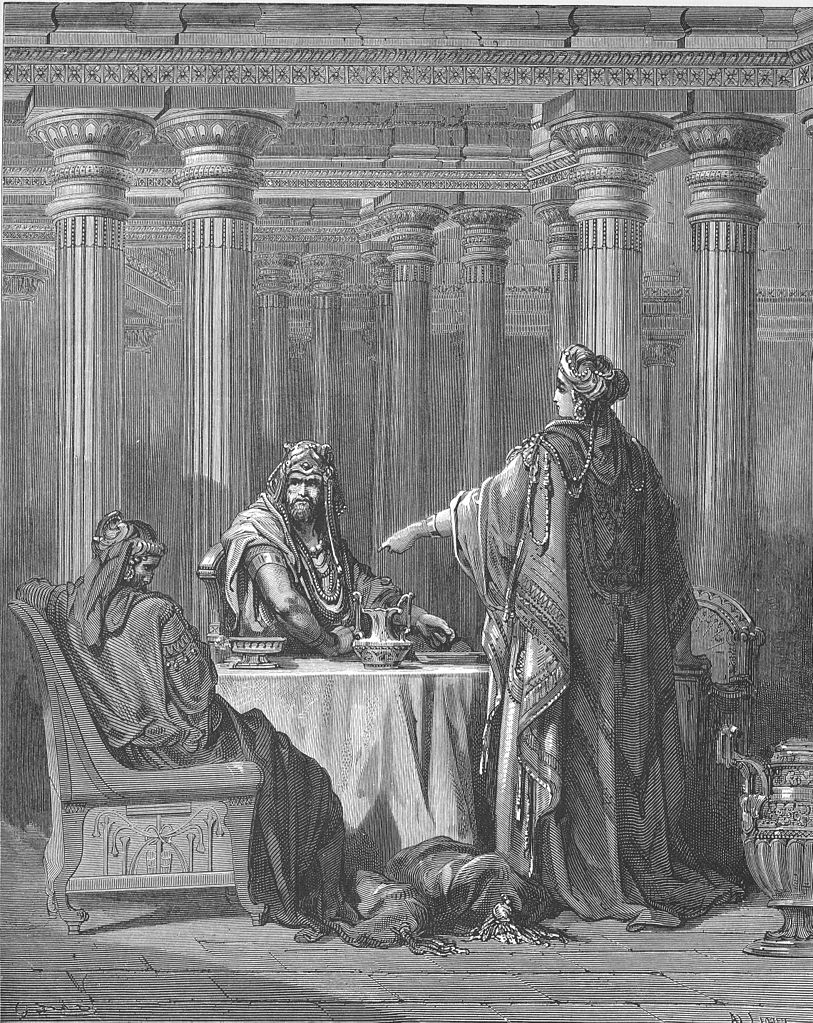

Esther confounding Haman by Gustave Doré, Esther 7, Bible.Gallery

Artwork Description

Martin Luther once expressed his desire for the non-existence of Esther and her book, a sentiment echoed by others in subsequent times. Their objections revolved around the book's perceived exclusivity, vengeful spirit, omission of God's name, and its portrayal of events on an earthly plane. However, it's widely acknowledged that even if the name of God isn't explicitly mentioned, His divine influence is evident. The most unassuming reader, linking Ahasuerus' dispute, the sleepless night, and the suspenseful lot-drawing, cannot help but discern the workings of divine Providence in the final outcome. This subtlety may serve to reinforce the notion.

As for the book's exclusivity, it is essential to consider the context of the period when these events took place. The vengeful feelings portrayed should serve as a cautionary example rather than a model for emulation.

There are also profound and inspirational aspects within the central character of the story, who was immortalized by Handel's genius and sanctified by Racine's piety. Esther exhibits remarkable patriotism and unwavering self-sacrifice when she proclaims, "I will go in unto the king, and if I perish, I perish." Her courage is further evident in her bold confrontation with the king's favored advisor. The artist accurately captures the grandeur of the architecture, Esther's resolute posture, the king's escalating fury, and Haman's dejected countenance, leaving nothing exaggerated in this depiction.